Ecowas' dilemma: Balancing principles and pragmatism

West Africa's regional bloc faces disintegration after failed sanctions against military regimes

Bamako, Mali, 1 February 2024. Supporters of the military junta and of the Alliance of Sahel States attend a rally. Photo: Hadama Diakité, EPA.

The decision by Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger to leave Ecowas reflects the bloc’s failure to address security and humanitarian issues in the subregion. It is also a result of people losing faith in Ecowas’ leadership after years of complacency and inconsistency in championing its democratic principles. Pragmatic dialogue with the member states currently run by military regimes will be crucial if regional collaboration is to be revived. And defending democratic values will be crucial if civilian rule and popular trust are to be restored.

By Kwesi Aning and Jesper Bjarnesen

When Ecowas, the Economic Community of West African States, was founded in 1975, it focused (as the name implies) primarily on promoting economic integration. But over the years – and notably following the revision of the Ecowas Treaty External link, opens in new window. in 1993 and the adoption in 2001 of its supplementary protocol on democracy and good governance

External link, opens in new window. in 1993 and the adoption in 2001 of its supplementary protocol on democracy and good governance External link, opens in new window. – democracy promotion has become a critical area of concern. However, it has been a significant challenge to ensure that member states comply with democratic norms, especially over the past three years, as Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali and Niger have all experienced democratic reversals. The four military juntas currently in power have used popular mobilisation against growing insecurity and systemic corruption as justification for the unconstitutional changes of government. In response, Ecowas has sought on the one hand to enforce compliance with its democratic norms, and on the other to involve the three junta-led Sahel states in ad hoc cooperation to ensure continuity in the security initiatives intended to deal with the growing threat of jihadist movements in the Sahel. As a consequence of this delicate balancing act, negotiating the pitfalls created through the inconsistent enforcement of its democratic ethos has undermined the organisation’s credibility. Nearly 50 years of integration processes are under threat of significant reversal.

External link, opens in new window. – democracy promotion has become a critical area of concern. However, it has been a significant challenge to ensure that member states comply with democratic norms, especially over the past three years, as Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali and Niger have all experienced democratic reversals. The four military juntas currently in power have used popular mobilisation against growing insecurity and systemic corruption as justification for the unconstitutional changes of government. In response, Ecowas has sought on the one hand to enforce compliance with its democratic norms, and on the other to involve the three junta-led Sahel states in ad hoc cooperation to ensure continuity in the security initiatives intended to deal with the growing threat of jihadist movements in the Sahel. As a consequence of this delicate balancing act, negotiating the pitfalls created through the inconsistent enforcement of its democratic ethos has undermined the organisation’s credibility. Nearly 50 years of integration processes are under threat of significant reversal.

Six military takeovers in three years

Over a period of nearly six years, between the ousting of Burkina Faso’s President Blaise Compaoré in October 2014 and the coup d’état in Mali in August 2020, there was not a single undemocratic change of government in West Africa. For this subregion, where many countries have a history of civil war and violent conflict, this was a period of remarkable stability. Shortly after the Burkina Faso uprising, which was prompted by President Compaoré’s attempts to amend the constitution and extend his 27 years in power even further, Ecowas considered a proposal to restrict presidential mandates to a maximum of two terms in office; but after opposition from Togo and Gambia, the idea was abandoned in May 2015 External link, opens in new window.. Since then, the democracy projects of the organisation’s member states have faced several challenges which have contributed in no small part to the resurgence of coups d’état: between 2020 and 2023, the subregion experienced six successful military takeovers, with Ecowas seemingly powerless to reverse them.

External link, opens in new window.. Since then, the democracy projects of the organisation’s member states have faced several challenges which have contributed in no small part to the resurgence of coups d’état: between 2020 and 2023, the subregion experienced six successful military takeovers, with Ecowas seemingly powerless to reverse them.

Ecowas’ supplementary protocol on democracy and good governance External link, opens in new window. provides specific guidelines shared by all member states. It focuses on the development of constitutional state-based rule of law, the strengthening of democratic processes and mechanisms, and common principles of good governance. Its adoption in 2001 marked a turning point in Ecowas’ political construction: it went from dealing mainly with economic integration to focusing also on the consolidation of fundamental democratic principles, such as the separation of the three branches of government; the decentralisation of power away from the office of the president; the depoliticisation of the armed forces; and the strengthening of electoral systems.

External link, opens in new window. provides specific guidelines shared by all member states. It focuses on the development of constitutional state-based rule of law, the strengthening of democratic processes and mechanisms, and common principles of good governance. Its adoption in 2001 marked a turning point in Ecowas’ political construction: it went from dealing mainly with economic integration to focusing also on the consolidation of fundamental democratic principles, such as the separation of the three branches of government; the decentralisation of power away from the office of the president; the depoliticisation of the armed forces; and the strengthening of electoral systems.

Through the adoption of different protocols, regulations and conventions, Ecowas sought to embed democratic norms in the subregion, contributing to democratic and multi-party transitions in the 1990s and early 2000s – a development that was tantamount to a political renaissance. Since then, democracy has been reduced to the holding of elections, which more often than not are tainted by violence and abuse of human rights. The provisions of the supplementary protocol were expected to be internalised by member states, acting as building blocks for institutionalising democratic values. However, pervasive and persistently low levels of economic growth and democratic backsliding without intervention by Ecowas meant that, as an organisation, the bloc gradually lost its moral authority and thereby inadvertently contributed to the creation of an environment that enabled the reappearance of coups d’état in the subregion.

Break-out states under military rule

The resurgence of military coups in West Africa since 2020 marks the end of a decade during which popular mobilisation was the predominant tool for challenging democratic backsliding. Inspired by the wave of uprisings in North Africa in 2011–12, West African citizens took to the streets across the subregion, resulting in notable concessions by Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal and the end of Blaise Compaoré’s 27-year reign in Burkina Faso. In August 2020, a small military faction led by Colonel Assimi Goïta exploited the mass mobilisation of the 5 June Movement against President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta to seize power in Mali. The popular and broad-based dissatisfaction was largely a result of the endemic problem of corruption and nepotism within the Malian state bureaucracy; but it also had to do with the worsening security crisis in the country, caused by the escalating violence perpetrated by jihadist insurgencies in its northern half.

The destabilising effects of the expansion of jihadist violence caused similar political dissatisfaction in neighbouring Burkina Faso and Niger. In Burkina Faso, despite winning re-election in 2020 by a comfortable margin, incumbent President Roch Kaboré was ousted by a military takeover in January 2022; the junta, led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damiba, cited the country’s deteriorating security situation at the hands of jihadist groups as its main motivation. In both Mali and Burkina Faso, reshuffles within the military leadership are often referred to as additional coups, with Assimi Goïta replacing transitional Interim President Bah N’Daw in Mali in May 2021, and Captain Ibrahim Traoré replacing Paul-Henri Damiba in Burkina Faso in September 2022.

In July 2023, Niger followed suit when a junta led by General Abdourahmane Tchiani toppled the democratically elected government and ousted President Mohamed Bazoum, allegedly in response to rumours that the president was planning to replace Tchiani as head of the presidential guard. Although all three countries face serious security crises at the hands of jihadist insurgencies, the political contexts differ significantly. For example, while the coups in Mali and Burkina Faso seem to have been spurred unequivocally by the regional security crisis, the coup in Niger also reflected an internal power struggle within the ruling elite. This is illustrated by the difference in military ranks: the mid-ranking junta leaders in Mali and Burkina Faso ousted most of the military leadership that formed part of the president’s inner circle, whereas General Tchiani ensured his own political survival when it became challenged by the civilian political elite. Despite these differences, the unconstitutional changes of government in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have shared a similar degree of popular support, primarily due to the lack of tangible progress in the fight against regional jihadism by the preceding civilian governments and their international partners. The coups, and the three juntas’ overt criticism of Ecowas – which is accused of being both inefficient and too dependent on European patronage – have added considerably to the pressure on the regional organisation.

Ecowas’ loud but toothless response to the coup d’état in Niger in July 2023 is symptomatic of the institutional inertia and bureaucratic-technical missteps that have undermined the organisation’s credibility. First, it suspended Niger’s membership of the organisation, imposed sanctions, closed borders, cut off the electricity supply (via Nigeria) and threatened to use military force if the coup leaders failed to reinstate the lawfully elected president. However, Ecowas lacked the support, the wherewithal and the institutional strength to follow through on its threats of deploying its standby force. Eventually, at a summit of heads of state and government in Abuja, Nigeria, in December 2023, Ecowas decided to set up a committee External link, opens in new window. to engage with Niger’s military junta and other stakeholders, with a view to agreeing on a transition roadmap that adheres to the bloc’s principles and the establishment of transition organs, as well as to facilitating the creation of a transition monitoring and evaluation mechanism to work for the speedy restoration of constitutional order. This decision, however, has been overtaken by events in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. In September 2023, those states formed an Alliance of Sahel States (Alliance des États du Sahel, AES), and in January 2024 they announced their intention of withdrawing from Ecowas.

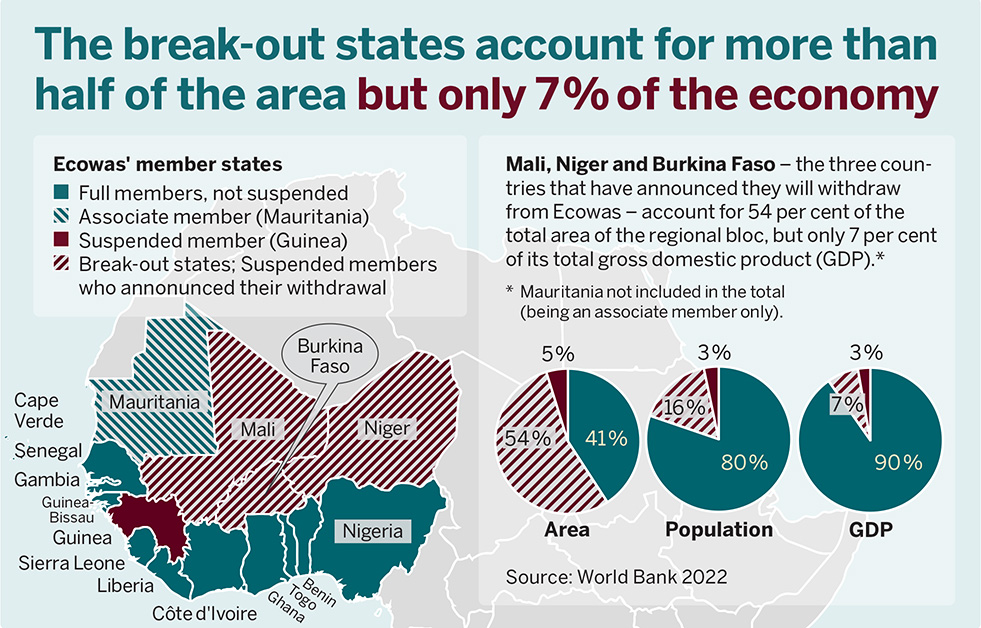

External link, opens in new window. to engage with Niger’s military junta and other stakeholders, with a view to agreeing on a transition roadmap that adheres to the bloc’s principles and the establishment of transition organs, as well as to facilitating the creation of a transition monitoring and evaluation mechanism to work for the speedy restoration of constitutional order. This decision, however, has been overtaken by events in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. In September 2023, those states formed an Alliance of Sahel States (Alliance des États du Sahel, AES), and in January 2024 they announced their intention of withdrawing from Ecowas.

West Africa’s waning security architecture

The AES was established as a security alliance in the wake of regional jihadist violence. The threat of withdrawal from Ecowas altogether should be understood in large part as an extension into the political domain of the inherent concerns regarding regional security, and as a clear rejection of the region’s existing security architecture. The relative success of regional security cooperation in response to the civil wars in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea Bissau in the 1990s and early 2000s – under the banner of the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group, or ECOMOG – has given way to a gradual decline and loss of influence in international military interventions. In 2003, Ecowas was present in the intervention to de-escalate the civil war in Côte d’Ivoire (in the form of the ECOMICI mission), but the regional bloc’s role was significantly reduced in relation to the UN- and French-led contingents. The tendency continued during Liberia’s second civil war, with the Ecowas (ECOMIL) intervention playing second fiddle to the UN-led (UNMIL) intervention. The only significant exception to this gradual decline in influence and leadership was the mobilisation in the wake of Gambia’s contentious elections of 2016–17, when the Senegalese-led ‘Operation Restore Democracy’ arguably forestalled incumbent President Yahya Jammeh’s unconstitutional claim to remain in power and ensured a bloodless transfer of power to the election’s legitimate winner, Adama Barrow.

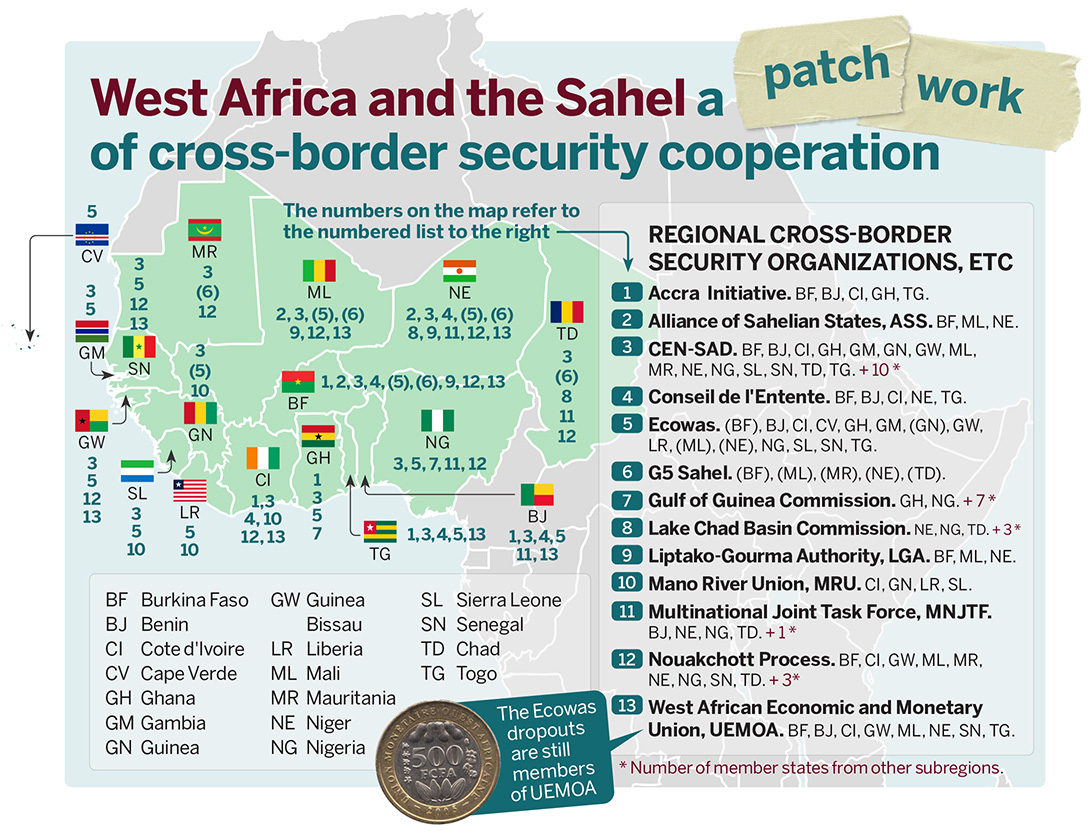

The gradual decline of Ecowas’ role in international peacekeeping missions over the past two decades has added pressure on the overarching African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), which is intended to institutionalise peace and security measures at the African Union level. A case in point is the attempt to establish the G5 Sahel joint force to bring the five central Sahel states (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad and Mauritania) together in the fight against regional jihadism. Although the overall intention of bringing peacebuilding closer to the regional context was sound, inadequate funding and complications in the G5 Sahel mandate vis-à-vis the UN- and French-led missions undermined the collaboration from the outset. With the failure of MINUSMA and Operation Barkhane, the G5 Sahel could have been an avenue for a more sustainable regional security collaboration; but any residual hope of the G5 Sahel taking the lead in regional security operations evaporated when the military regimes of the AES withdrew from the collaboration in 2022 and 2023.

Partially in response to the slow progress of the G5 Sahel, the Accra Initiative was launched in September 2017. It includes three of the former G5 Sahel states (Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger) plus the five coastal neighbouring countries of Benin, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Togo and Nigeria (with observer status). The Accra Initiative is mainly geared to preventing the spill-over of regional terrorism and other transnational organised crime from the Sahel to neighbouring border areas, and it is seen as more genuinely founded on regional interests – in contrast to the G5 Sahel, which over time has increasingly come to be regarded as a European project. With the military takeovers in three of its most strategically important member states, however, the Accra Initiative is facing similar legitimacy problems.

In the aftermath of the suspension of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger from Ecowas’s wider cooperative security framework, those states signed a mutual defence pact, using as an institutional reference the Liptako-Gourma collaboration under the G5 Sahel and the long-standing Liptako-Gourma Authority (a subregional organisation established in 1970 to promote regional integration). The Liptako-Gourma charter establishing the AES aims at a collective defence and mutual assistance framework that obliges the signatories to assist one another – including militarily – in the event of an attack on any one of them. In addition to the regionally based alliance, the perceived ineffectiveness of international interventions such as the MINUSMA mission and the French-led Operation Barkhane has contributed to Mali’s decision to seek other external partners, such as Russia.

The end of Ecowas as we know it?

If the announced withdrawal of the AES states is realised, Ecowas will undergo an unprecedented transformation, and will see its subregional scope significantly curtailed. This would signify the failure of Ecowas as an enforcer of regional norms. Its protocol on democracy and good governance, its political principles and other documents that seek to provide normative frameworks and blueprints, and to impose limitations on state action will need re-examination. In a reformed regional framework, non-compliance must be dealt with in a consistent manner.

It seems more likely at the time of writing that the AES breakaway countries will remain members of Ecowas in the long term. This could unfold in one of two ways. Either the military juntas will reach a negotiated agreement on remaining, or the countries will rejoin once they return to civilian rule. At an extraordinary summit of Ecowas in February 2024, called in response to the AES states’ declaration of withdrawal, the chair, Nigerian president Bola Tinubu, announced that Ecowas was lifting sanctions on Niger External link, opens in new window. in a new push for dialogue and to keep the ‘unity’ of the organisation. This illustrates the regional bloc’s readiness to engage with the military regimes and to offer concessions, in order to prevent fragmentation. Whether or not Ecowas has had its territorial scope permanently reduced, the future of regional collaboration in West Africa still has the potential to become an important force for democracy and stability in the region, simply by enforcing its own rules and values consistently. And the current crisis should be taken as an opportunity to engage in critical reflection on the shortcomings of the regional organisation, and as an occasion for genuine reform.

External link, opens in new window. in a new push for dialogue and to keep the ‘unity’ of the organisation. This illustrates the regional bloc’s readiness to engage with the military regimes and to offer concessions, in order to prevent fragmentation. Whether or not Ecowas has had its territorial scope permanently reduced, the future of regional collaboration in West Africa still has the potential to become an important force for democracy and stability in the region, simply by enforcing its own rules and values consistently. And the current crisis should be taken as an opportunity to engage in critical reflection on the shortcomings of the regional organisation, and as an occasion for genuine reform.

Lurching from one ad hoc response to the next, Ecowas has deployed the whole gamut of policy options available in its toolbox. From sanctions targeting coup leaders, to threats of imminent military intervention, the organisation has misread the popular mood in the subregion and has dusted off normative frameworks that are no longer fit for purpose. With the formation of the AES, Ecowas now has several competing and overlapping transnational security frameworks. These include the G5 Sahel (now G2), the Multinational Joint Task Force, the Accra Initiative and Ecowas’ overarching security framework. Ecowas’ inability to appreciate the drivers for change that are propelling the actions of the three junta-led states has led to further fragmentation.

In the interest of restoring civilian rule in the AES and of rebuilding the lost legitimacy of Ecowas as a regional enforcer of democratic norms, it is essential that the organisation manages to strike a fine balance between the pragmatism required to engage with the subregion’s military regimes and an insistence on the fundamental democratic values and principles embedded in its protocols. West Africa’s international partners, including the European Union and its member states, face a similar challenge to prevent the further political and diplomatic isolation of the Sahel states and embrace a renewed collaboration on more equitable terms. The Nordic countries in particular, with their record of promoting democracy and good governance, should seize the opportunity and take the lead in such dialogue, following France’s withdrawal from the subregion.

NAI Policy Notes is a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. It aims to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-reviewing processes.

About the authors

- Kwesi Aning is Security and Political Analyst at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Ghana, and NAI Associate. He specialises in peacekeeping economies and peacebuilding strategies.

- Jesper Bjarnesen is Senior Researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI). His main areas of research are migration, mobility, displacement and informal labour recruitment through wartime and peace in West Africa.

How to refer to this policy note:

Aning, Kwesi; Bjarnesen, Jesper (2024). Ecowas' dilemma: Balancing principles and pragmatism : West Africa's regional bloc faces disintegration after failed sanctions against military regimes. (NAI Policy Notes, 2024:1). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2939 External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.

On a related note

Researcher: “ECOWAS is now in damage control mode”

Join our podcast as we discuss Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger's announced exit from ECOWAS, deepening divisions in the Sahel. We analyze the roots of the rift, effectiveness of ECOWAS' sanctions, junta leaders' tactics, anti-colonial sentiments, the role of foreign powers and the humanitarian impact.